"EXPLORING SJØLTEKTUR: AN INTERVIEW WITH ARTIST MORTEN ALMAAS". ROBERTA ATRASTE

Places can reveal hidden layers of a city, challenge routine ways of seeing, and expose unnoticed details or underlying social and economic dynamics.

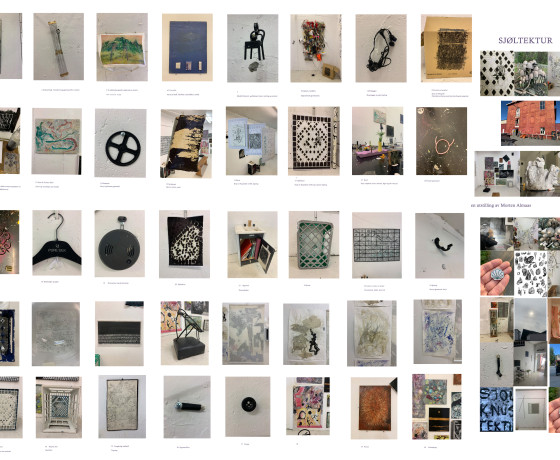

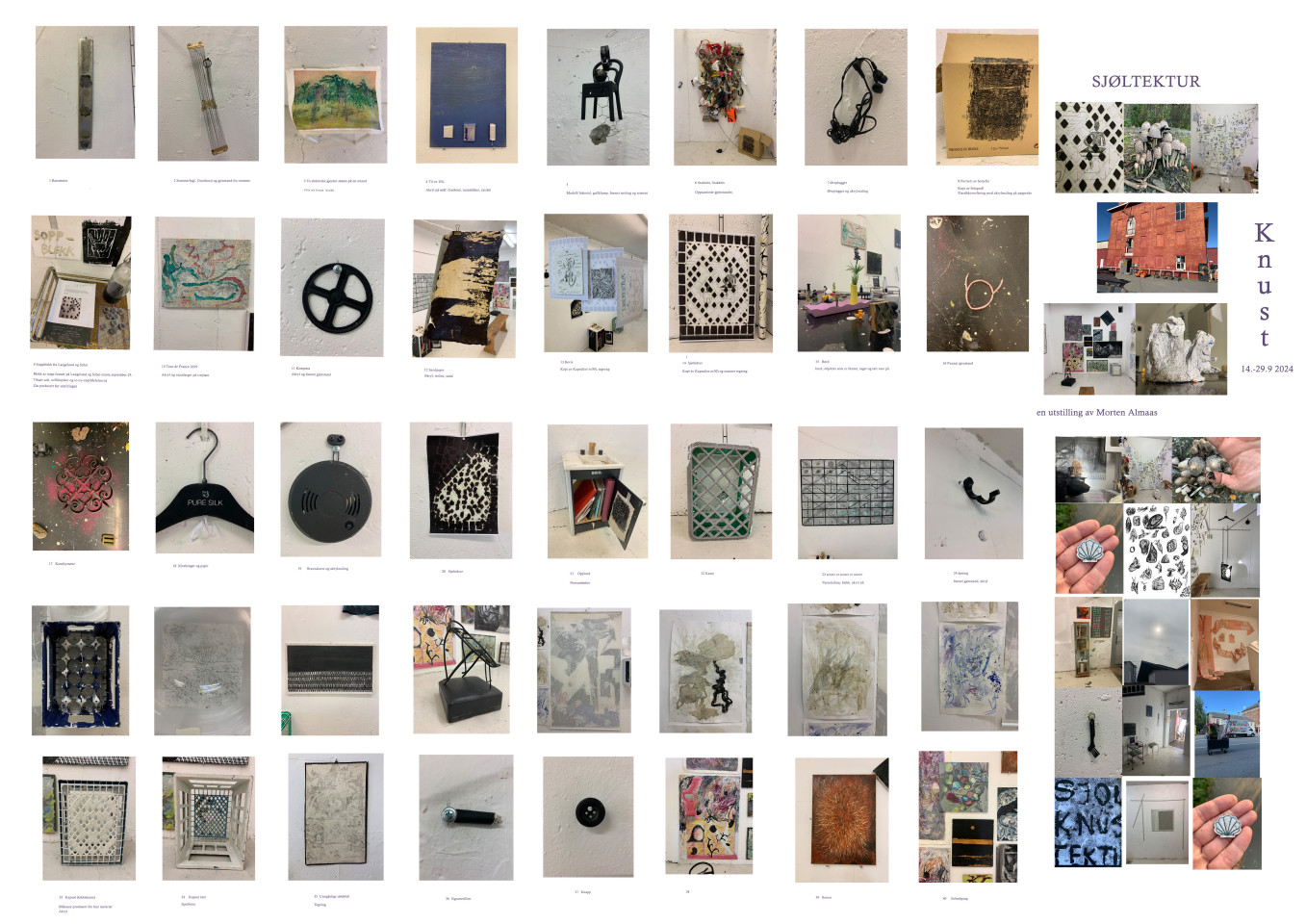

This was the introduction to the KUNO course "City out of Sight," held from September 16 to 20, 2024, in Trondheim, Norway. After exploring Trondheim and the Knust gallery exhibition SJØLTEKTUR, I had the chance to sit down with artist Morten Almaas in a school cafeteria the next day. Our conversation took us back to 2015, a time when Morten, amid personal transitions, shifted his focus from writing to drawing, which soon felt like a more natural form of expression for him.

For Morten, drawing isn't just a technical skill; it's a means of self-discovery. Over the years, his work with materials like acrylic, papier-mâché, and wood glue has focused on their behavior and his interaction with them. Instead of aiming for specific outcomes, Morten embraces the journey, welcoming unexpected discoveries.

For him, art is more than the final product—it's about creating a space where both the artist and the viewer can connect and experience the work in their own way.

Roberta: You’ve mentioned writing as an early passion. Do you see any connections between writing and drawing, like in the use of black and white or forming a narrative? Or do you feel they’re completely different creative processes?

Morten: For me, it's both similar and different. With drawing, I feel very free, but with writing, I feel constrained. I struggle with the fixed meanings of words and find it hard to break away from that. Writing feels tough, almost brutal, and very concrete to me. When I write something, it feels like it reveals more about me than I intend, and that makes sharing it difficult.

Drawing, on the other hand, doesn’t have that weight for me. I can create and share drawings without overthinking my motives or analyzing them. I usually learn about my own work from how others react to it, rather than dissecting it myself. So, I both try to avoid analyzing my art and let others’ interpretations guide me.

Drawing often follows structured rules, like writing does with punctuation and grammar. When you start drawing, are you focused on representing reality, or is your thought process different? What are you trying to express in your work?

Rules, information, and knowledge usually come later for me. I draw every day, so there's always something new I'm working on. Then, when I take a course or talk to someone, I might learn a specific detail, like about perspective. Seeing someone demonstrate it—rather than just looking at a photo—really helps it click. It connects because I've already been doing it, but I didn’t have the words or understanding for it yet. That’s when I truly learn, once I can match the information to what I’ve already practiced.

So… you could say that drawing for you is a form of learning.

Yes, I remember this being well explained by a student[1] at Funen Art Academy. In Odense, Denmark, who graduated this year. I don’t recall his name, but he said something that stuck with me: he draws not to show what he’s thinking, but to *see* what he’s thinking. Through drawing, he realizes what’s going on in his mind. That’s what I find important about drawing—it helps me understand myself.

For me, drawing has always been foundational to my practice. It always comes first. An artist friend and mentor once told me that everything in human history began with drawing. Whether it was a stick in the sand or something else, drawing has always been there. I see it differently from other art forms because it's so deeply connected to who we are as humans—our height, our hands, our vision—everything.

I guess it's not always very pleasurable to see what you are thinking about.

I’ve learned a lot about my ability to focus and how my attention works. It’s hard for me to hold onto a thought, so repetition doesn’t come naturally to me. In my drawing, I’ve had to really work on this. I notice how long I can stay focused before my mind starts to wander, and that’s been a big part of my learning process.

I often use a pointillism technique, where I make dots, and the movement of my hand determines the drawing's outcome. It’s really an exercise in staying focused, without thinking about what the final image will be. I just focus on the process—adjusting pressure, repeating small movements. But after about a minute and a half, I start to feel restless, and my movements get bigger. So, I’ve had to work on staying within the limits I set for myself while also learning to embrace the uncontrolled moments that happen when my mind starts wandering. Does that make sense?

It seems like your approach to drawing is closely tied to time, as each piece reflects a specific moment rather than forcing it to match a precise idea or timeframe. So, how do you decide when a drawing is finished?

This question has been a big part of my process. Naturally, if I’m doing something I enjoy, I tend to keep going and going until I’m exhausted and lose track of what I’m doing. I’ve had to work hard to control this because I don’t want to work that way. While some people thrive on that kind of high, almost manic energy, and create amazing things, I’ve realized it’s not sustainable for me. So, I’ve been trying to find a better balance.

What does the form of control look like?

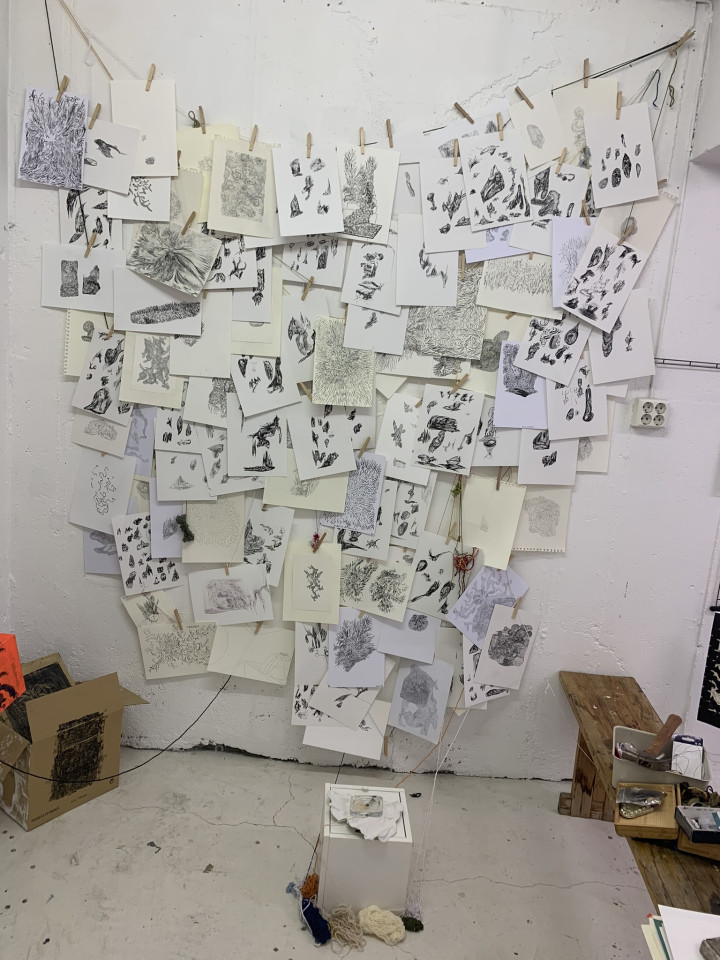

In my exhibition, there’s a wall with a lot of small drawings, often A4 papers with just a small cluster of dots. I think of this as the “beginnings” wall, where I start something but, for whatever reason, don't take it further. Over time, these unfinished pieces have become more interesting to me than the ones I fully complete. When I finish a drawing according to my idea or technique, it can feel boring because I already know the outcome. But these beginnings, these leftovers, are more intriguing because they feel less controlled.

As for when to finish a drawing, I don’t have a clear answer. I try to trust something deeper than my immediate thoughts or reasoning, relying more on a larger instinct or feeling rather than just my head’s judgment.

Do you ever return to a painting or drawing after considering it finished? Do you often revisit and continue pieces, or do you have a routine of leaving them behind and starting something new?

What I’ve realized since being at the Academy of Art is that I tend to work in piles. I accumulate a lot of things, and then at some point, I dive into the pile, sorting through it to see what I’ve been working on. I like to create my own categories, almost like doing archival work—screening and organizing everything. A lot of this comes from a desire to control and have an overview of it all, but I have to remind myself that’s not really possible. There’s too much, and I don’t have the capacity to keep track of everything. So, I try to trust my instincts and just go with the flow. I feel like I’m building my experience by doing this.

Have you noticed any types of categories?

Yes, and this is something I’ve noticed in my drawing. I go through different phases, like periods where I focus on drawing faces, and these phases can last a long time because my learning process is slow. Since 2015, I’ve had several phases of drawing faces. There's always a shift between drawing what I know—like deciding in advance that something will be a face—and simply starting a drawing without a clear plan. This shift is connected to my personality, mood, and thinking, though I don’t have it fully figured out yet. It seems to be influenced by something personal in my life.

I see two main categories in my work: figurative and, for lack of a better term, abstract. I also keep coming back to landscapes, where I focus on creating depth, making things go inward instead of popping out on the two-dimensional surface. Creating a sense of space or room on the paper is really satisfying for me. When I realized I could open up a whole scene with just a horizon line, it was like a revelation. But I’m still not entirely sure what that means for me.

When you mention opening up a room on paper, it reminds me of what you said during your exhibition about using the placement of images to create a sense of space. Would it be fair to say that this idea of opening up space also interests you in your curatorial practice?

Yes, absolutely. I’m more interested in creating an experience where viewers can step into the artwork, rather than just standing and looking at a single object. Even if it's just visually, I want people to spend time in the space the artwork creates. The physical hole or opening isn’t the important part—it’s the way it shapes the space, allowing viewers to enter into it.

There's an old Chinese myth about Wu Tao, a painter who was isolated in his room. He painted a mural of a landscape on the wall, then supposedly stepped into it and disappeared. That story has stuck with me for years, and I think about what it could mean in terms of creating immersive experiences in art. I want art to be something people experience, not just look at.

In your exhibition, it’s interesting how you start with an introductory space, like the foyer, and then lead into a separate room upstairs. Was this purely a practical choice to use all the available spaces, or was it also about creating an experience—almost like an overture, setting the mood for what’s to come, similar to the beginning of a musical composition?

The foyer is a bit specific to the space and comes from my collaboration with Anders Elsås, who runs and co-curates the exhibitions there. But I also like to create an entrance or initiation space in the gallery, and I’ve done this before. It helps establish a sense of narrative and, in part, makes the space feel more welcoming and relatable for the audience. It’s a way of saying, “This can be a journey, with a beginning,” but if you try to follow a traditional narrative from A to B, you’ll likely get lost, as there’s no clear storyline that progresses in that way.

So there is no chronological narrative.

No. And I see this as kind of an imitation of life. It's analogous to life. We have a beginning, we have an end but things aren't really arranged that way.

How has your approach to different materials and techniques been involved in this exhibition?

For me, the most important thing is to just keep creating something every day. That’s my main focus. A few years ago, I had a breakthrough with painting, where I could just sit down and start without overthinking it. But with sculpture, it’s different. Last year, I began working with papier-mâché, and as I got into sculpting, I found myself facing expectations about what sculpture "should" be—ideas about technique, art history, and symbolism.

I’ve been actively trying to let go of those expectations and focus more on simply looking and creating. One of my professors, Anne Karin Furunes, who has a background in architecture, has been really helpful in pointing out the qualities in my work. For example, when I made a model of a house, she was interested in how it was sinking and bending—qualities that come naturally with paper over time.

Now, I focus on the relationship between my process and the materials. I’m interested in the tension between what I bring to the material and what the material naturally does on its own. That’s where I feel my work is currently centered.

So do you like to create the tension or ease the tension?

It depends on the material. I try to let the material guide me, exploring its qualities—how far it can be pushed, when it breaks or changes, how flexible or elastic it is. That process of discovery is satisfying for me. As I get to know the material, it starts to suggest new ideas and possibilities, even when I’m not aiming for a specific outcome.

I enjoy experimenting and creating new ways of working. If not, I just make a pile—there’s a saying that if you put one stone on another, eventually you'll have a pile. I find that idea significant because it reflects something essential about our lives as humans. Even when digging a hole,

you create a pile. It's a simple yet important marker of our actions, with geographical and symbolic meaning.

What was the question again?

So this digging and making piles of categories, can I go back to that?

Last year, I became really interested in the idea of categories while working with papier-mâché. As I shaped the paper, I noticed I was creating small piles of leftovers—bits of paper and glue on my desk. At the same time, I was also working with snails, which made me think about the separation of things into two categories. There’s the pile of leftovers and the final artwork, but I found myself more interested in the leftovers.

I started focusing more on what was left behind after creating, rather than the finished objects themselves. This idea connected to my work with snails, specifically the ones with shells, where you have two components: the snail and its house. That separation of things into two categories became a key theme for me.

Does this idea of noticing the negative space or perhaps the unseen connect with your work, your subconscious, or even your activities in the city?

Yes, I think so. I'm really interested in the structures of things. Through drawing and painting, I became fascinated with certain theories, especially from a design professor—I can't recall his name right now—who wrote a famous book called Power of the Center[2]. It's about how our vision works and how we physically structure the world around us. For example, the horizon line isn't something that actually exists; it's something we create because it's important to how we see.

This professor developed a system, a drawing that explains how we structure the world visually, and I use that a lot in my work. It's one of the foundations of my drawing process, following those lines. Sorry, I lost track—what was the question again? I had more to add.

Negative space…

Yes, I think "negative space" connects to a new way of thinking for me. Lately, as I walk around the streets, I feel like I’m living in an architect's model or a white cube—similar to how a city can feel like an exhibition, just on a larger scale. I’m not entirely sure what this means yet, but it’s something I’ve been reflecting on as I’ve started working with gallery spaces and white cubes. It feels like I’m walking in negative space, and if you looked at our surroundings on a flat surface, you’d see that we’re living in a kind of negative space. I’m still processing what this means and if it's significant, but it’s been on my mind.

Have you faced any challenges working in the current exhibition, considering it's a kind of "white cube" space, which can feel isolated or detached from everyday life?

It's definitely a white cube. I come from a non-art background, so before I started at the academy or spent time at the Knust gallery, I had no real connection to this kind of space. I was just like a regular art viewer, curious about what it all meant. I knew artists worked with white cubes, but I didn’t understand much about them. Early on, I learned a lot about the white cube, including an interesting article about how the specific color that defines it, titanium white, is actually produced here in Norway.

The titanium white used in white cubes comes from two large mines in Norway, and this started about 100 years ago. It changed a lot, from how we use toothpaste to how art is displayed. Originally, the white cube was seen as neutral, a space that didn’t represent anything specific. But now we know it’s not neutral at all; it’s very representational. Elevating art objects on pedestals in a white cube doesn’t automatically make something art, in my opinion.

I've worked with white cubes because they are practical. We have a great, large gallery here at the Gallery Kit [Editor's Note: The Art Academy of Trondheims student-gallery], which is a white cube. At first, it was exciting—like a blank sheet of paper. It gave me creative freedom. I don’t feel that my art is misrepresented in a white cube, but I do notice how it affects my audience. Many of my visitors aren’t necessarily interested in art—they're friends or curious people—and the white cube can feel cold or unwelcoming to them. That’s something I’m trying to work against.

What are your observations, have you perhaps noticed people being nervous?

In a similar exhibition I did in January, I had a bigger room and set up a small office space in the corner where I could observe people without them noticing me. I watched how they moved through space. In my exhibitions, I like to scatter things around, so visitors have to make a conscious choice—they can get an overview, but they have to focus on specific pieces. This approach seems to work for many visitors who aren't sure how to behave in an art space and may feel they need to act a certain way. I often notice a sense of relief when they realize they can take their time and explore freely.

However, I’ve also noticed that my artworks don’t reveal themselves easily—you have to engage with them and invest meaning into them. It’s not always the most straightforward art to experience.

But you have also made the deliberate choice not to write a classic curatorial text.

I've tried different approaches—sometimes I’ve made detailed lists with proper titles and names, and other times, like in this exhibition, I've included more random text, some of it specific to the show and some not. I'm exploring whether this expectation to title things is necessary because I don’t always feel like giving titles to my work. I think naming objects can sometimes shift them into another realm, and I’m not sure we fully understand the names of things that exist in the realm of art.

Can you tell me more about your exhibition title?

The title Sjøltektur is a word I came up with—it just appeared one day. I immediately associated it with concepts like architecture, the self, and self-enforcement, which I find interesting. My exhibition is also tied to the place itself, Knust, and what it has become in recent years—a gallery and cultural meeting space that Anders has created almost single-handedly.

The word "sjøl" comes from my dialect and means "the self." It’s foundational to the DIY culture in my neighborhood and the art practices I’m part of. I wanted to highlight that, which is why I chose the word.

Knust is a shared, open space—free for the public, with no tickets. Anders is incredibly generous with his time, always opening the space or even playing a concert if someone asks. To me, that generosity is part of the art itself. So, while I had to give the exhibition a name, Sjöar Tektur felt fitting for what I wanted to convey.

In the exhibition, you reversed the fabric, exploring the idea of what's underneath. Can you explain the thought behind this?

Yes, it's actually turned inside out and upside down. I even considered titling it Inside Out, Upside Down because it reflects something I’ve noticed in my practice—I'm drawn to exploring what's beneath the surface. Lately, I’ve been working with thick layers of acrylic and wood glue, peeling them off to see what's underneath. This idea of flipping things and looking through them keeps coming up in my work.

In this case, I turned the painting for practical reasons and realized I preferred the reverse side. The original side felt too figurative and the acrylic too dry, attracting dust and becoming flat and boring. The reversed side had more life and interest to it, which is why I went with that.

I was immediately drawn to the composition in your work, both in individual pieces and how they're arranged in the room. Could you talk a bit about your approach to composition?

When it comes to composition, I feel like that’s where I have some real knowledge about painting, drawing, and art. I’ve gone through processes that have given me a solid understanding, even if I don’t always have the words to explain it. Over the years, through improvisation, I’ve developed an instinct for composition. I can create something and later look at it, understanding the choices I made and why I made them.

Maybe composition functions as a framework for the unconscious.

I want people to be able to wander freely with their eyes, not being led to one specific thing. You can focus on something, but then your eyes should move around. I often use spiral compositions because they give a sense of movement, making the objects feel less confined by gravity. This reflects how I think people should experience art—freely, without being limited by preconceptions. Art isn't just about knowledge; it's a human activity for everyone.

What do you focus on before thinking about solutions? What's important to you in that earlier stage?

Yeah, what is that? I want to work with what’s called the "unthought"[3]—the material that exists before our thoughts are fully formed or structured in our minds. That’s where I want to be, where I like to focus my work.

[2] Rudolf Arnheim (1904—2007) was Professor Emeritus of the Psychology of Art at Harvard University and Emeritus Professor of Psychology at Sarah Lawrence College. He was the author of many books, including Art and Visual Perception, Film as Art, and Visual Thinking.